'The ship that sank an island'

On the stormy night of 22 March 1973, on its way from South Uist to Oban, the Loch Seaforth struck rocks in Gunna Sound between the Isles of Tiree and Coll, with over 40 passengers and crew on board.

All survived, without a single injury. She was towed to Gott Bay off Tiree, where she sank, blocking the island's harbour for six weeks.

'Scots on the Rocks'

The accident was the worst possible start for Caledonian MacBrayne, created three months earlier when David MacBrayne and the Caledonian Steam Packet Company amalgamated. But since then, its safety record has been "impeccable", says a historian.

The story was reported round the world: 'Scots on the Rocks' headlined the Buffalo News in New York. It was told as a Hebridean farce, worthy of the Compton MacKenzie comic novel, and film, Whisky Galore. But it is also a tale of terror, the closest one survivor ever came to death in his 72 year-long life.

Here we tell both sides for the first time, thanks to contemporary newspaper reports, island memories collected by Dr John Holliday and others in the Tiree Historical Centre's An Iodhlann newsletter, and now the incredible testimony from a witness still alive to tell the tale.

Before heading to Tiree to mark 50 years since his ordeal, John Jordan tells us his story, the full story, in print for the first time.

"attachment_896689" "aligncenter" "300"]

The MV Loch Seaforth at Mallaig in 1971.

The MV Loch Seaforth at Mallaig in 1971.

“She is a bad ship – a rogue"

She deserved a better end. Built in 1947, the 1,100 tonne, twin screw MV Loch Seaforth was ordered by MacBrayne's for the important run from Mallaig and Kyle of Lochalsh to Stornoway on the Isle of Lewis.

The first vessel in the fleet to be fitted out with radar, she was also the biggest MacBrayne ship until car ferries came in 1964.

She served the Mallaig-Kyle-Stornoway run until 1972, when she was replaced by the car ferry, the MV Iona, and assigned to the Oban-Coll-Tiree-Barra-Lochboisdale run, with occasional visits to Colonsay.

In her later years, the gathered a reputation as accident-prone, after grounding in Mallaig harbour in 1965, then colliding with Mallaig pier the following year, and grounding on a reef at Kyle the next day. In 1971 she hit the island of Longay, off Broadford, and her passengers had to be rescued by a passing launch.

“She is a bad ship – a rogue," said one crewman to The Scottish Daily Express in 1973: "She sits too high in the water and this makes her prone to windage.” Another crewman said: “The ship is narrow and wallows a lot. She is not good in a tight corner.” Then came the fifth, and final, mishap.

"attachment_896758" "aligncenter" "300"]

MV Loch Seaforth and MV Loch Arkaig at Kyle of Lochalsh in 1971.

MV Loch Seaforth and MV Loch Arkaig at Kyle of Lochalsh in 1971.

The fifth, and final, mishap

In the week of March 22, 1973, 22-year-old surveyor John Jordan was living in East Kilbride and working on the rocket range on the Isle of Benbecula. Usually, John travelled the two-hour ferry route on the MV Hebrides from Uig to Lochmaddy.

But that week he had exams and took the overnight mail boat MV Loch Seaforth, which left Lochboisdale on South Uist around 10pm, stopped in Barra after midnight, and arrived in Oban at 8am the next morning.

"It was my first time sailing from Lochboisdale, and the first time I had the car on it," he told The Oban Times. "Things were different back then. It was as much a mail boat as a ferry. It did not carry many passengers. Everything was loaded onto the deck with nets.

"There was no roll-on roll-off in those days! It was quite basic. You went to your berth, and woke up the next morning. I was quite tired. I thought I would get a decent night.

A loud crash

"It was a rough night," he recalled. "It was a force 10 gale. The only reason we were sailing was because it was forecast to improve. There was a lot of banging, a lot of noise once we left Barra and got into the Minch. I did not get much sleep after that.

"There was one particularly loud crash, but I just thought it was another thing that had gone wrong. There had been so much that night. I had never travelled that route before, in the middle of the Minch, in the middle of a force 10 gale. I just assumed the noises were all about the weather.

"After five to 10 minutes, a crewman said: 'You had better get up on deck quickly, because we have run aground.' It was 5.30am. I managed to get partially dressed, but not water proofs. I just had my trousers and jacket on. We were all gathered on deck. There were roughly 13/14 passengers, plus crew. I was half asleep.

"attachment_896686" "aligncenter" "300"]

John Jordan, 72, describes one of the scariest nights of his life, abandoning the wrecked MV Loch Seaforth into a lifeboat on stormy seas.

John Jordan, 72, describes one of the scariest nights of his life, abandoning the wrecked MV Loch Seaforth into a lifeboat on stormy seas.

"We abandoned ship"

"Once they decided everyone was there, they decided to go onto the lifeboats. It was about 6am when we abandoned ship. It was pitch black.

"There were four lifeboats on the boat. At least three were in the water. We were behind one of the lifeboats. The front boat had an outboard motor. We were being towed by the boat in front, in heavy seas. They headed the boat into the wind to prevent it capsizing, and that was all they could do. We were using the oars just to keep the boat stable.

"We could not do anything. They were open rowing boats, totally exposed to the weather, and everything that the sea was going to throw at you. One moment you are on the crest of a wave and the next moment at the bottom, and then the next one is on top of you. You could not see anything because the seas were so rough.

"Nobody knows we are here"

"Beside me was an army sergeant and his wife. She was still in her night clothes. They had just run up without getting any layer of clothing on themselves. There was a stewardess. She was trying to look after a couple of kids. She kept her arms around the children, and tried to shelter them from the spray.

"You do not go through something like that and not be scared, but you are trying to keep the rowing boat on course and afloat. The guy I was sitting next to was the radio operator. I asked if an SOS signal went out. He said: 'No. There was no time.' The despair kicks in then. Nobody knows we are here.

"There was no sign of the storm abating. We were with a boat heading into the storm, into even deeper water, and not knowing what was going to happen. None of us knew anything. No conversation was taking place. You could only see what was happening in front of you. It was easier for us to have a conversation between here and Oban than out in the Minch on the boat.

"attachment_896761" "aligncenter" "230"]

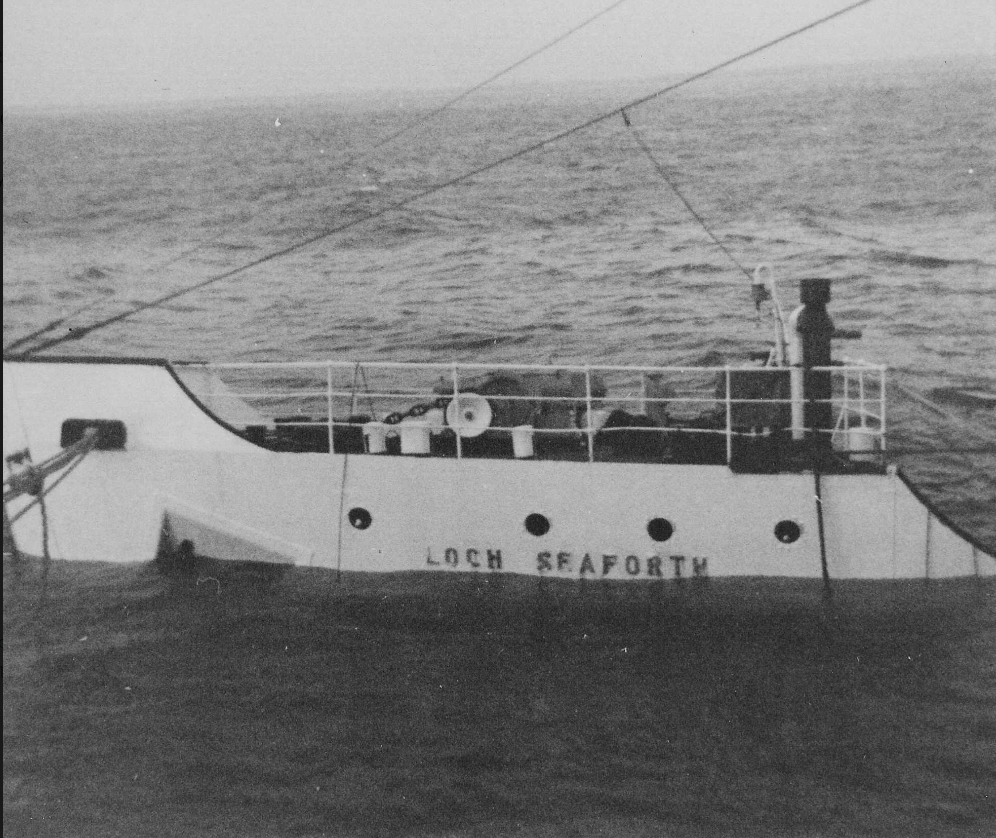

A photograph of the stricken MV Loch Seaforth in Gunna Sound, in The Evening Standard dated March 22 1973.

A photograph of the stricken MV Loch Seaforth in Gunna Sound, in The Evening Standard dated March 22 1973.

"If you capsize the boat, that's it"

"Everybody has got an oar. You are trying to use it to the best of your ability. If you capsize the boat, that's it. Everybody is gone. You are wondering if anything you do is going to make any difference.

"Is this it? Are we going to go down? Are we going onto the rocks? Or are we going to get picked up? But the weather is so bad, are they going to be able to do that? The storm did not look like it was abating at all. How is this going to end? There was not much room for optimism. I just put it to the back of my mind.

"At daylight between eight and nine, a fishing boat found us. But we could not transfer onto the fishing boat, because it was so rough. The fishing boat got a line out to the lead boat and began towing us. That took us to Scarinish [on the Isle of Tiree]. It took us over an hour. It was still stormy."

"Sheer relief"

How did he feel when he reached land? "Sheer relief, at the fact we were okay. It is very hard to describe if you have not been in the situation. It was a very close call. I still cannot believe no one lost their lives.

"We were out there for four hours, in an open rowing boat, in the middle of the Minch, in a force 10 gale, half of that time not knowing if you will be picked up, or if anyone knows anything is wrong.

"We were taken to Scarinish Hotel. There we found out the crew members that had been in the lifeboat were in the hotel before us." On the open seas, he did not know the fate of that third lifeboat.

"A hell of a risk"

"They had seen lights on the island," John said. "They decided to risk it and went for the beach, knowing there were lots of rocks there. They must have taken a hell of a risk. It is all rock to get to those beaches. You are taking your life into your hands. They found their way onto the beach and to the house, and raised the alarm.

"The Scarinish Hotel took us for a shower, a bath. We were soaked to the skin. There was not a dry part of your body. At 12, I got dry clothes to put on. It was like a scrum with reporters there. How they got there I do not know.

"CalMac sent out another boat which took us from Tiree to Oban later that evening. My memories of that night were zero - probably a reaction if you are in an accident. It does not register until hours afterwards.

"attachment_632064" "aligncenter" "300"]

A Tiree beach.

A Tiree beach.

"They did not get everyone"

By coincidence, two senior CalMac officials had also been on board when the ship struck rock: Mr NJD Whittle, general manager of the company, and Mr Morris Little, the chairman.

Mr Little told The Oban Times then: “While no-one expected this to happen, it was an enlightening experience to be present and see for ourselves the magnificent manner in which our crew reacted to the situation.”

But John recalled: "They did not get everyone." What happened next shocked everyone - again.

"Where did you come from?"

When the crew returned to save the stricken Loch Seaforth stuck on the rocks, they made an unexpected discovery. Not everyone had got into the lifeboats: they had left behind a passenger, who had slept through the shipwreck.

"Willie Miggin of Enfield, County Meath, was touring the west coast and was a passenger on that voyage," recorded The Sunday Post. "Wanting to lie down he found an empty cabin down below and fell asleep.

"When he awoke he was conscious of a ghostly silence throughout the ship. No throb, throb, throb of the engines. No footsteps or voices above deck. He knew the ship hadn’t docked. He could feel its sway as it ploughed through the water. Mystified, he left the cabin and walked along the corridors. Strange, not a soul in sight. He looked in the cafeteria – and stared goggle-eyed. It was empty too, with half-finished cups of tea and half eaten biscuits on the counter.

"attachment_896695" "aligncenter" "300"]

The MV Loch Seaforth after it sunk in Gott Bay. Photograph: the late Angus MacLean.

The MV Loch Seaforth after it sunk in Gott Bay. Photograph: the late Angus MacLean.

The Marie Celeste

"When he came up on deck, it was deserted. Now he really had the jitters. It was like the Marie Celeste. What calamity had befallen everyone? How could the ship sail without engines? He pinched himself to make sure he wasn’t dreaming. Gingerly he walked towards the bow. He nearly jumped out of his shirt when voices shouted, 'Ahoy, there!' He was being hailed by some men on the bridge. 'Where did you come from?' they asked. 'Never mind where I came from,' said Willie. 'Where has everyone else gone – and where are we going?'

"Willie was flabbergasted when he was told what had happened. The ship, the Loch Seaforth, was being towed by a tug. It had run aground on the rocks of Tiree. The crew had warned passengers to take to the lifeboats. They’d carefully ticked off every name on their berth list. Willie had been overlooked because his name wasn’t on the list, and his berth was supposed to be empty! He’d slept like a log through the whole hubbub of the drama. Imagine sleeping through a shipwreck!"

A costly mistake

The vessel was taken to the Gott Bay pier and tied up - a costly mistake, as it turned out.

"She should have been put around the side of the pier, but there was a MacBrayne’s chief of operations, and he thought there was no problem, and he over-ruled the skipper, which strictly speaking he couldn’t do, and said she must go on the front of the pier, and of course that was us cut off," Donniel Kennedy recalled to John Donald MacLean in 1998.

"The captain wanted to beach her, because he knew what would happen, but the top men aboard, they shouldn’t have taken over the captain, because he’s in charge of the boat. But they’ll be wishing now they did it," Donald Iain Kennedy told Bernie Smith and Dr John Holliday in 2012: "It cost them a fortune."

"attachment_896692" "aligncenter" "300"]

The MV Loch Seaforth submerged by Scarinish pier. Photograph: the late Angus MacLean.

The MV Loch Seaforth submerged by Scarinish pier. Photograph: the late Angus MacLean.

"A hole as big as a fist"

During the night, the boat started to take water more seriously.

"Engineers inspected the Loch Seaforth yesterday after she was towed by tug to Scarinish and reported that she had a buckled plate and 'a hole as big as a fist' under the waterline," said a newspaper cutting from March 23 1973.

"Throughout the night the list to port worsened and at breakfast time it was no longer safe for the crew to remain aboard. The crew had gathered belongings and equipment and were watching from the pier when the ship rolled over.

"An eye witness at Scarinish said today: 'She went over very slowly on her port side, her superstructure smashing against the pier. I don’t know how much damage has been done to the ship but it looks pretty bad.'"

"No one was on board," reported the Herald Express on March 23. "The chief steward and an engineer had spent the night on board but left when they heard a rumble and the ship started to move."

"The water just gushed in"

"We were on the pier that morning," remembered Donald Iain Kennedy in 2012. "We were supposed to [take off] half a million [pounds worth] of clams, shellfish and prawns on it, and we were all preparing to sling it off, and the next thing, she just went, right against the pier. The bulkhead gave way, the front part of the engine. The water just gushed in. Brand new Jeeps, and vans. They were all over the place. Gordon Donald made a song about it."

"She settled on her side in six metres of water the very next day, when the port-side cattle door became submerged," wrote Nick Robins and Donald Meek in The Kingdom of MacBrayne (2006). "At this point it was found some of her bottom plates were all but perished, the divers claiming they could push their fists through the plates in some places.

"The Loch Seaforth was beginning to suffer from decay of the poor quality steel used in her construction, which was all that had been available in post-war Britain when she had been built."

"attachment_896701" "aligncenter" "211"]

The Loch Seaforth and the puffer Glencloy carrying cargo. Photograph courtesy of Peter Knapman.

The Loch Seaforth and the puffer Glencloy carrying cargo. Photograph courtesy of Peter Knapman.

The sunken wreck sinks Tiree

The wreck was now blocking most of the pier. Passengers for the ferry were able to embark in a small boat from the slip beside the pier, but large cargo movement - cars and cattle - was virtually impossible.

"The Columba (now the MV Hebridean Princess) made a special run to Tiree until the Claymore took over the service. The puffer Glencloy was chartered to take cargo from Oban to Coll and Tiree. Loch Seaforth ... blocked the pier so that passengers had to be ferried ashore using the ferryboat Iona," explained the book West Highland Steamers.

"During April the pier continued to be blocked, the Glencloy kept up the service for general cargo, but vehicles and cattle could not be loaded. The company then chartered the Dutch vessel Johanna Buitalaar for special cattle shipment from the Tiree sales, she being just able to squeeze between the sunken vessel and the pier."

"He just had to run for it!"

"Folk were going out with Land Rovers, going up and down Gott Bay picking up packets of cigarettes," recalled Donniel Kennedy in 1998. "They were ruined, the seawater. But they were pulling out the coupons, and throwing away the cigarettes! There must have been a lot of fish on board, and the odd barrel of beer came out of it.

"And of course there was a float. And someone got the idea that these floats had survival gear, including a very good expensive knife, so he tried to open the float, and immediately the thing burst into life, inflated and whistles and sirens, he just had to run for it!"

"The tide line of Gott Bay was covered with dead fish," remembered Fiona MacKinnon in 2012. "A number of tables and chairs from the Loch Seaforth came into the houses, and, for some reason, lots of burns medicine."

"It’s amazing how fast she went off the beach too," Donald Iain Kennedy said in 2012. "We got the lifeboats. I got one. A schoolmaster from outside Oban got the one with the engine in it. Paint everything, all over the place. All the life rafts. They landed below the church in Kirkapol there. They took them. The police were after them!"

"attachment_896704" "aligncenter" "211"]

The Loch Seaforth, the relief CalMac ferry Claymore, and the cargo ship Glencloy. Photograph courtesy of Peter Knapman.

The Loch Seaforth, the relief CalMac ferry Claymore, and the cargo ship Glencloy. Photograph courtesy of Peter Knapman.

"We took all the whisky"

"When she hit, the first thing they did was send down a diver to clear the bar. To make sure folk didn’t hurt themselves more than anything, diving down for stuff," Donniel Kennedy told John Donald MacLean in 1998.

"We took all the whisky and everything off," recalled Donald Iain Kennedy in 2012. "The directors, that were in, there were six of them in. I picked one [bottle] up and one of the top ones said, “Take a dram. It’s only going to get dumped anyway. We’re only taking it off the boat in case of a scandal” he said, “In case anybody gets drowned trying to get it.” She was still at the pier. There were a couple of divers in."

"It was a very hectic hour"

"It was a strange time travelling back to Tiree on the Claymore after the Seaforth sank," recalled Peter Knapman to The Oban Times this month. "The sinking coincided with my parents purchasing a house in Tiree and my father had arranged to bring a van load of furniture only to find that the Seaforth was blocking access to the Tiree pier.

"The van was left stranded on the pier in Oban with a promise that it would be delivered to Tiree on the Glencloy. Somehow the Glencloy squeezed itself between the sunk Seaforth and the pier! The van was unloaded with the instruction - if you are not back in an hour then the van stays in Tiree. It was a very hectic hour but we managed!"

"It took over six weeks for the stricken vessel to be moved," explained West Highland Steamers. "She was lifted with a giant barge and moved to the sands of An Tràigh Mhòr, Gott Beach, where she was patched up.

"On May 11 the giant floating crane Magnus III (chartered from Risdon Beasley of Southampton) arrived and lifted Loch Seaforth, moving her to the beach. She was patched and refloated, then left in tow for Troon where she was scrapped by the West of Scotland Shipbreaking Co. So ended the career of one of the best ships of the Stornoway service."

"attachment_896698" "aligncenter" "300"]

The Seaforth raised by crane. Photograph: the late Angus MacLean.

The Seaforth raised by crane. Photograph: the late Angus MacLean.

"A party for the salvage crew"

The ill-fated Loch Seaforth was to be sold for scrap in Troon, where she would fetch between £10,000 and £12,000 – salvaged from Tiree in an operation that cost her owners, MacBrayne’s, “tens of thousands of pounds”.

"In a massive salvage operation the Loch Seaforth was lifted right out of the water by a mammoth German crane and beached half a mile away – out of the way," reported The Scottish Daily Express on May 24 1973. "Her owners said she would never sail under her own power again.

"Colonel Patrick Thomas, chairman of the Scottish Transport Group, said during a visit to Tiree: 'We have lost a lot of money and, what is equally important, one of the units of our fleet. We must stress, however, that the boat will not be abandoned on the beach'."

"The salvage operation was praised by Colonel Thomas: 'The men have done an absolutely fantastic job. They moved the boat in 48 hours flat. We cannot stress how grateful we are to them.'

"The community showed its appreciation of the removal of the boat by throwing a party for the salvage crew – it was a British operation with some German equipment and crew.

"Scarinish turned out in force for the dance – the local accordion band vied with the Tiree Piping Society for musical honours. Compliments were paid in English and German. Songs were sung in both languages. And the saga of the Loch Seaforth ended in noisy and joyful camaraderie in the village hall – with the hulk of the island ferry bathed in moonlight on the beach in Gott Bay."

“You and I fought one another in the war”

Hugh MacLean of Barrapol remembered that party well, telling Dr John Holliday in 1998. "The ones we looked upon as our enemies. I met one or two of them. And there was one in particular, what a gentleman. A German. And he opened his heart to me. That was years after the war. The time the ferry, Loch Seaforth, sunk at the pier over there. They had to get a salvage vessel from the continent to pick her up of the ground over there. One of the crew, I met him at a dance over there, what a gentleman.

"I remember, we were sitting in the committee room, we had our uniform on, we were in the pipe band, you see. I was sitting there and the rest of the boys were around, and this fellow came in and there was an empty seat, closer to the door than the seat I was in, and he approached me.

"'May I sit?' he asked. 'Yes, You’re very welcome,' I said. He had this smile on his face. He’d be about my own age at that time. And he turned round eventually. 'I suppose,' he said. His English was a wee bit broken but still he was very good just the same.

"'I suppose,' he said, 'you and I fought one another in the war.' 'Oh!' I said, 'You’re German.' 'Yes,' he says, 'I’m German.' Now it was a German crew they had aboard that vessel. 'No,' I said, 'I wasn’t in the armed forces. Maybe I fought you in some other way, producing food.' And he opened his heart to me. 'What’s wrong,' he says. 'We’re the same people. Why does this happen,' he says.

"We were taught to hate these men"

“Oh! What a nice chap. He was from Holstein, in the east part of Germany, at the foot of Denmark. And he was praising our music. 'It’s like the music,' he says, 'that I’m used to in my own homeland.' 'Do you have music like this?' I said. 'Yes, in the part I come from, in Holstein. It’s very like our music.' And he stayed with me there, and I enjoyed his conversation. A very nice fellow. And eventually he said, 'Would you excuse me, I’d like to go out. I’ll be back to see you,' he said, 'but I’d like to go out at the moment.'

"And when he come back we were playing the pipes for the audience, and we went back to where we were in the committee room and he walked in with a big bottle of good whisky on him and put it on the table in front of us. 'That’s from me,' he says 'to the boys.' 'Oh!' I said, 'thank you very much.' I said. 'We didn’t expect [that].' 'Well, it’s the least I can do. I enjoyed your conversation.' He was a very nice fellow, a German, and we were taught to hate these men!"

After the party, the MacBrayne ferry was towed by two tugs to Troon for scrappage, in an operation that took 21 hours, reported The Scottish Daily Express on May 24 1973.

"attachment_896710" "aligncenter" "201"]

A bull loaded into the Glencloy. Photograph courtesy of Peter Knapman.

A bull loaded into the Glencloy. Photograph courtesy of Peter Knapman.

A final mystery, and a Ford Escort

As she departed Tiree's shores, the Loch Seaforth behind her an enigma in her wake. "It was funny when she left, when the salvage team took her away, she was minus a prop," Donald Iain Kennedy said in 2012. "They never found it."

Her cargo was also lost. "My car was on that boat. It was a Ford Escort. I can even remember the registration plate. It was brand new. It was a company car. That went down as well. There was TV coverage two or three days after. You could quite clearly see the car bobbing around on deck. I never got the car back. It was scrapped because it spent too long under water.

"I did not take the Lochboisdale to Oban route for another year. I thought I would go back to Tiree. I have a lot of unanswered questions." If you want to share your memories of the sinking of the Loch Seaforth with John, or meet up with him on his trip to Tiree on March 22 2023, please contact him via us at editor@obantimes.co.uk.

"We cannot blame CalMac"

"This was the last significant calamity that has affected CalMac," said Andrew Clark, author of The Making of MacBrayne (Stenlake Publishing), a major new study of David MacBrayne Ltd, from its 19th century origins to its present status as CalMac's parent company.

"That is the only real blot, and we cannot blame CalMac for it because it was taking over a fleet of old boats. She was on a run she was not used to. It was under the cover of darkness. It was in a notorious stretch of water. There is a rock that sticks up and it is not visible.

"Its safety record is impeccable. CalMac provide a safe, comfortable journey for thousands of passengers every day, in waters that are not hospitable. People ought to be glad there are cancellations, because masters are using their judgement not to risk customers' lives in these treacherous situations."

"attachment_896713" "aligncenter" "300"]

The Loch Seaforth sunk by Scarinish pier. Photograph courtesy of Peter Knapman.

The Loch Seaforth sunk by Scarinish pier. Photograph courtesy of Peter Knapman. Latest News

JOBS

Distribution Craft Apprentices - Scotland - SSE

Sign up to our daily Newsletter

Permission Statement

Yes! I would like to be sent emails from West Coast Today

I understand that my personal information will not be shared with any third parties, and will only be used to provide me with useful targeted articles as indicated.

I'm also aware that I can un-subscribe at any point either from each email notification or on My Account screen.

You may also like

Latest News

JOBS

Distribution Craft Apprentices - Scotland - SSE